As a student in the 1990s I was often torn between pursuing 3D computer technology and more traditional ceramics and sculpture. Computer graphic tools were in their early stages of development at the time, not nearly as accessible as they are today, but I saw their potential. At the same time, I became interested in the Italian Futurists, who are, of course, pillars of the historical avant garde. Boccioni’s work in particular became a personal symbol for me of the potential within a fusion of art and technology. The Futurists championed the machines of their day.

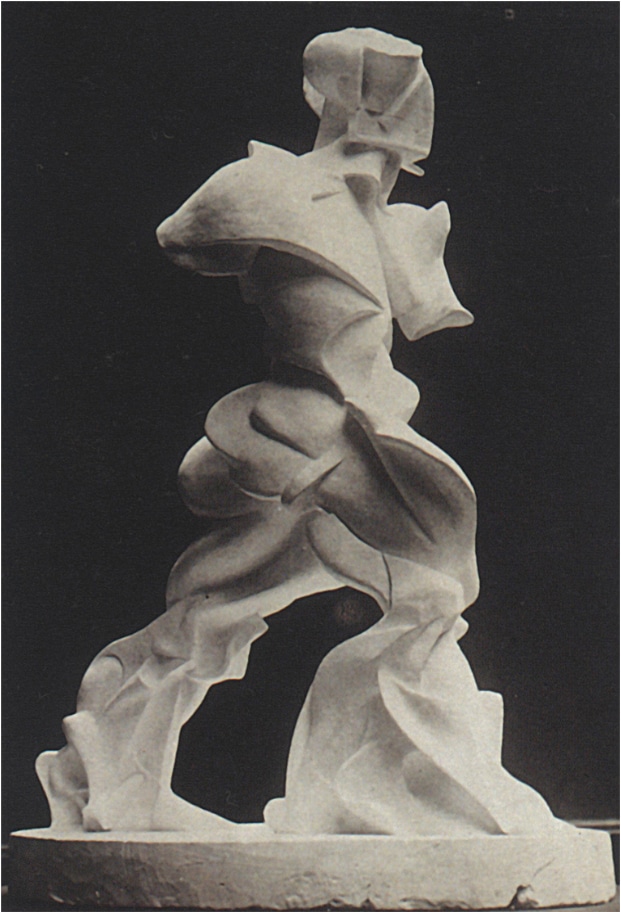

Boccioni’s work with plaster was progressive as well as challenging. His sculptures are such complex forms. Many of them have cracks and seams where they were probably made up of blocks initially. Boccioni talked about continuous forms, in reference to his sculpture, and I’d imagined that the types of unbroken seamless forms could be developed further with computer graphics. Bringing Boccioni’s art into the realm of computer visualisation also allows further development of his art theory of force-lines through, for instance, animation. Force-lines, by the way, are dynamic lines in painting, through intuition, that open up the figure, and enclose the environment within the object. Boccioni wanted to abolish closed finite lines and the self-contained statue. Boccioni also describes force-forms which are more concerned with centrifugal direction and the potentiality of the real living form, which is where I think the dynamic movement and power comes from. The sculptures show their intention to move, rather than hold one static position.

I remained fascinated and wanted to understand more about Boccioni’s sculptures. However, as I researched, I couldn’t find all that much to go on at the time. It’s worth saying this was before the Internet. I knew Boccioni had painted most of his life and I was aware he had made three sculptures before his tragic death. In the early days of my enquiry I was drawn to and felt an affinity with Boccioni’s seminal sculpture, Unique Forms. It reminded me of a figure walking through water with streams of flowing currents that so beautifully capture the liquid’s resistance to this forward movement. To think the work was made 100 years ago is still astonishing.

It was some years later in 2007 that I used some of the new digital tools to make my own digital computer model of Unique Forms. Primarily this was a way of understanding how Boccioni worked. I took this direct approach of copying the work from photographs as there was no documentation of his practice and techniques as a sculptor.

I became fascinated with how, exactly, Boccioni made such a huge leap in his practice. At this point in 2007 I didn’t know about the other lost sculptures. It seemed to me he went from being a painter and realising a few 3D works, two of them quite small, to producing Unique Forms, which is an extremely accomplished sculptural work.

What exactly this process–this leap–involved prompted my trip to Italy in 2007 and my discovery of eight other lost sculptures. It’s a great story but also a bit confusing. Boccioni only had one exhibition during his lifetime. This took place in 1913 and featured a total of 11 plaster sculptures. All of these were destroyed. However, three works, Unique Forms, Development of a Bottle in Space and Antigraceful were remade by repairing the fragments and then casting them years after Boccioni’s death. I wanted to understand and recreate the eight that were lost and then present them altogether, effectively restaging Boccioni’s exhibition of 1913. I had no idea how I would ever achieve this ambition but I have made this my aim ever since. This is developing in parallel with my own practice. I am determined to contribute to Boccioni’s legacy in light of the artist having given so much inspiration to myself and many others.

That has been one of the difficult things to explain to friends, family and the public. The project clearly spans research, digital tools and new 3D printing technologies. I’ve collaborated with others on the production, and curation, held drawing workshops in galleries and universities for animation students. Initially I wanted to develop my skills as an artist and digital sculptor as I was preoccupied with learning through the process or reconstruction. The project has changed a great deal over the years, developing organically from a successful Kickstarter campaign to something that continues to grow and surprise me. Unique Forms is arguably the most important Futurist sculpture but its story isn’t yet complete. So the narrative I’m trying to reconstruct is about the steps and artworks that led to this apex.

I made a digital computer model of Unique Forms in 2007. This helped my understanding of Boccioni’s work. The experience would allow me to use this as a basis to interpret missing or unclear areas of the poor quality photographs of Spiral Expansion, the only surviving evidence of this work. One might think of it as reverse engineering, but of course I had to develop some more artistic sensibility to achieve the desired quality and finish.

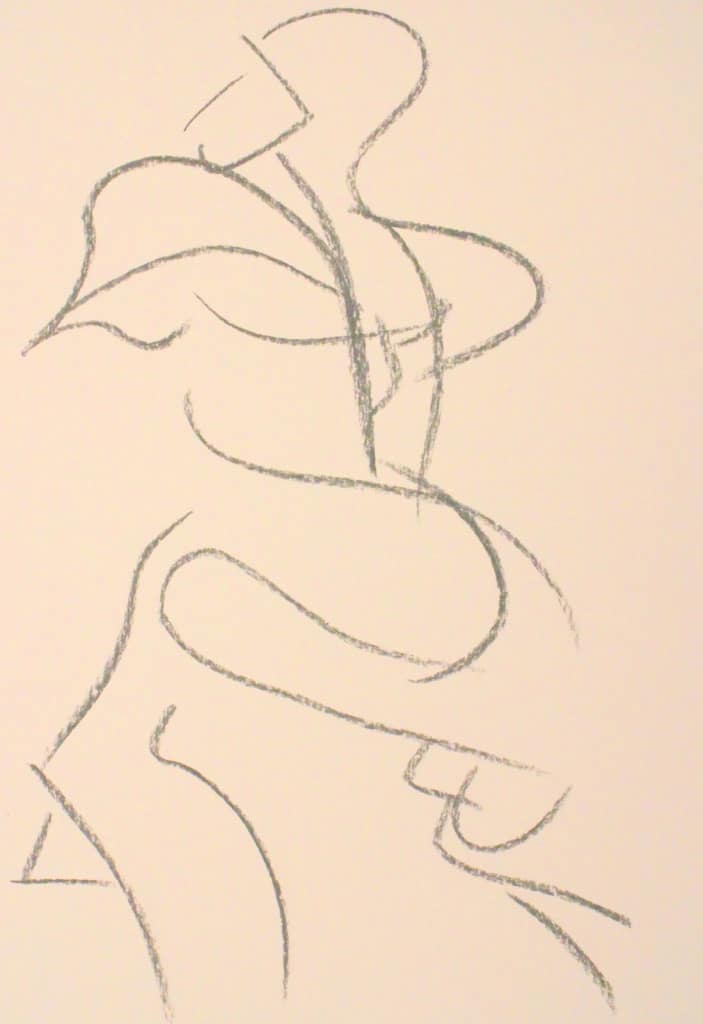

Referencing Boccioni’s drawings and sketches was important. They were useful in combination with the photographs, helping me to see the artist’s intention which was not always evident in the photographic detail. I also adapted my drawing style to help me experience, by my own hand, the mark making and Boccioni’s force-lines.

It’s another great story as I have read and heard differing accounts over time. One explanation is that Boccioni’s sculptures were stored in a courtyard after his posthumous exhibition in 1917 and were smashed by workmen anxious to clear out this area for another show. Another explanation is that a roof collapsed on the sculptures while they were stored at Boccioni’s mother’s house. The most accurate description is that in 1927, most of his plaster sculptures were destroyed by the sculptor Piero da Verona who had been storing them in his studio. This latter account seems the most likely as it is mentioned in the article, ‘Recasting the Past: On the Posthumous Fortune of Futurist Sculpture’ which is written by Maria Elena Versari, a leading expert on Boccioni.

Art and design school taught me how to approach problems and to adapt the foundational skills of drawing and to learn new techniques where needed. Industry taught me about process and technology through digital tools and production. The project wouldn’t have been possible without these experiences, especially failing and trying new ways. Research was key. I bought every book I could find on Boccioni. The photographs of Spiral Expansion were poor quality. There was one good photograph from the right side (from the sculpture’s point of view). The others were a mix of studio shots, just small fragments. The scrutinising of this source material and using Photoshop to enhance it took countless hours.

A core approach however was photographing Unique Forms in 2007 and making a digital sculpture of the work. I used a 3D software tool called Zbrush, which is very powerful and more like working with digital clay. This was before photogrammetry and 3D scanning were available. On reflection, using photographs forced me to look and interpret the shapes that would be a good basis for hours of looking intensely at the old photographs of Spiral Expansion. It made me more self-reliant on my own artistic practice, especially the digital sculpting skills needed to interpret the missing areas.

I used my digital sculpture study of Unique Forms as a reference template in the background of the software tool, similar to layers in Photoshop, or how transparent paper can be used to draw over a background image. Unique Forms is what Boccioni arrived at. I kept this in mind as I was working backwards from this work. This was akin to a creative devolution process to Spiral Expansion. With this latter work, Boccioni isn’t quite there in terms of the forms being as refined. This was important. For example, there is a small shape on the head that extends a few centimetres. Due to the angle of the photograph it’s hard to say where the shape was centred. Initially I placed it more central and it looked pleasing to my eye. However the position of the shape felt a little too perfect. So I made the position of this small piece slightly off centre, because Spiral Expansion is less streamlined than Unique Forms.

During the process I also brought in reference photos of Spiral Expansion which acted as a template. The process of digital sculpting is hard to explain. It is both additive and subtractive, adding like digital clay masses or taking them away, using a Wacom tablet and digital pen on the screen. Many of the digital brush tools, such as the rake brush and the clay build-up tool, mimic their real world counterparts. This effect has many advantages, but it lacks the tactile feedback of touch that traditional sculpting in clay provides.

3D printing has its own technical requirements, as does computer numerical control (CNC) milling. The computer controlled machines are similar to milling machines that remove material from blocks with rotary cutters. The CNC machines use the digital computer model I made to guide the removal of material to reveal the final sculpture. The material block to be milled could be a dense foam or even marble. 3D printing is an additive process, often plastic layers build one layer at a time, the 3D printer uses the computer model also as a guide. One advantage is consistency. All the sculptures share the same master digital file. I was glad I put so much detail into the digital sculpture, especially as I had no idea at the time that there would be a marble version of the sculpture made in Italy a year or so later. For an exhibition in London I also had Bakers Patterns in Telford make CNC foam sculpture that was 117 cm tall.

Determining this was one of the biggest challenges. The basic shape and form came quickly. But it was the details and quality that I kept pushing as I needed these to be good for a 117 cm tall sculpture.

When I created the Kickstarter campaign I was honest to say that my re-creation could never be 100% accurate due to the quality of the photographs. I felt if my work could capture at least 80% of the essence of Boccioni’s original then that would be an experience beyond anything available in the past 100 years. As I’ve developed Spiral Expansion and realised it in different materials, using diverse technologies, I’ve come to learn that Unique Forms has also been finished in a variety of materials in addition to the artist’s original white plaster version. Boccioni never saw a bronze cast of his sculptures as he died in 1916 and casts were first made in 1931.

When I was digitally recreating Spiral Expansions, in the final week or two of the process, I kept looking back and forth between the original but grainy photographs and my digital re-creation. I felt frustrated that there was now more detail in my digital sculpture as a whole than in the photographs themselves. It took me a few more days to realise that this was the best measure I was going to get and that it was ready for the fabrication stage.

I self-funded the project for a few months, and set up a Kickstarter campaign which was funded at just over £5,000. This allowed me to gauge if there was interest in the project and to pay for the small 3D prints that went out around the world to the Kickstarter backers as rewards. I was also able to produce the 117 cm full-sized sculpture to exhibit at Espacio Gallery in London.

The marble sculpture of Spiral Expansion was a wonderful surprise. It really came about through a generous collaboration. Around 2010 I’d been to Italy to meet with Enrico Dini of D-Shape, which is a large-scale 3D printing company with a track record for printing big concrete structures. We discussed the project of re-creating Boccioni’s lost sculptures. Enrico is a great supporter and friend. D-Shape worked with TorArt on a project to reconstruct Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph, using photogrammetry, 3D printing and robot milling. A half-size reconstruction of the Arch was shown in London in April 2016. I met Enrico at this time and by then I had completed a maquette of Spiral Expansion and so could show him this. Coincidentally, TorArt wanted to make Enrico a small marble CNC milled sculpture to mark the collaboration on their project. Enrico asked them to produce a small-scale version of Spiral Expansion and once TorArt learned about the project in more detail they decided to also make a full size 117 cm marble sculpture. That was fantastic to experience, and quite a surprise. This version of Spiral Expansion now resides in Italy. I couldn’t be happier as a result. It’s like the sculpture is at home. There were ideas and plans for showing the work at some future events, or commissioning other limited editions.

From the research and academics I’ve spoken to, there does not seem to be a Boccioni Foundation/Estate. As Boccioni died over 100 years ago, and the sculptural work was destroyed, it’s my understanding that there aren’t any legal implications. Less official, but more in keeping with Boccioni’s intentions, I’ve had to consider the choices I make for how my versions of his work are used. For example, a century ago Boccioni wanted to destroy the nobility of marble and bronze, yet his fellow Futurist Filippo Marinetti agreed to have Boccioni’s work cast in bronze in later years. The technical manifesto of futurist sculpture that Boccini wrote also stated that the movement would refuse the exclusive use of one material. And yet many of Boccioni’s own sculptures were exclusively plaster. So I try to keep these divergences in mind as they seem to provide some leeway. For me it is the quality and finish that are the main concerns.

I’m currently working with a foundry on bronze casts of Spiral Expansion that are 39 cm tall. I’ve finished creating a digital file of another of Boccioni’s lost sculptures, Abstract Voids and Planes of a Head (1913). This will be 3D printed at its original size. I’m also in conversation with another digital artist about collaborating on the others lost sculptures. I’ve already shown the work in London and Liverpool in galleries and universities, and hope to do more of this. My ambition is to recreate the exhibition of Boccioni’s lost sculptures, if time and resources allow.